1. The Image of a “Filthy” Middle Ages

Image: Portrait of an elegant lady holding a perfume bottle — Public Domain

Many people have heard the claim that “medieval Europeans never bathed and covered their stench with perfume.”

Stories about French noblewomen avoiding water and masking uncleanliness with fragrance are especially widespread.

As a result, the idea that the Middle Ages were dirty and that people lived without bathing has become almost common knowledge today.

However, this popular image is historically inaccurate.

It is true that during the 16th to 17th centuries, outbreaks of infectious disease and contemporary medical theories led people to believe that bathing in water invited illness, and public bathing declined for a time.

Yet from the 12th to the 15th century, bathing was actually highly common throughout Europe.

The stereotype of a dirty Middle Ages was later shaped mainly during the Renaissance and the Enlightenment, when intellectuals positioned themselves as the era of reason and light, portraying earlier centuries as an age of superstition and filth.

That biased perspective was passed down and became the modern assumption we accept today.

This article explores the misunderstood world of medieval cleanliness and hygiene.

2. Not Unclean at All

Image: “La toilette,” c.1880 — Public Domain

The idea that medieval Europeans were filthy is a misconception.

In reality, many households practiced regular washing and purification rituals.

Bathing, however, did not always mean soaking in a large tub as we imagine today. More commonly, warmed water was poured into buckets or basins, and the body was washed in sections.

Household manuals such as “Le Ménagier de Paris” (14th–15th century) and the English etiquette book “The Book of Nurture” describe noblewomen and servants adding herbs like sage, rosemary, and marjoram to bathwater for fragrance.

These herbs also had known disinfectant and calming properties.

For noblewomen, cleanliness was not merely about removing dirt. It symbolized status, education, and emotional refinement—a ritual to purify both body and spirit.

Through the use of aromatic herbs and water, medieval noblewomen cultivated a quiet and elegant culture of personal care.

3. Medieval Soap

Image: Castile Soap — An olive-oil-based soap created in Castile, Spain in the 12th–13th century. Still produced worldwide today — Public Domain

Soap was widely used in medieval Europe to maintain cleanliness.

Although early forms of soap existed in ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt, and the Romans scraped oil from their skin rather than using soap, soap production and use expanded significantly in the medieval period.

By the 7th century, soap-makers formed guilds, and cities in France and Italy traded high-quality imported soaps.

Aleppo soap, made from laurel oil and olive oil without animal fats, was a luxury product praised for its fragrance and gentleness to the skin.

In the 12th century, the technique reached the Iberian Peninsula, where it evolved into Castile soap, earning widespread acclaim.

Ordinary people, meanwhile, made simple soap by combining wood ash with animal fats and used it for everyday cleaning and laundry.

Fragrant luxury soap served the wealthy, while ash-soap represented the practical ingenuity of common households.

Within this soap culture, differing ideas of “cleanliness” reflected the social structure of medieval Europe.

4. Bathhouses as Social and Healing Spaces

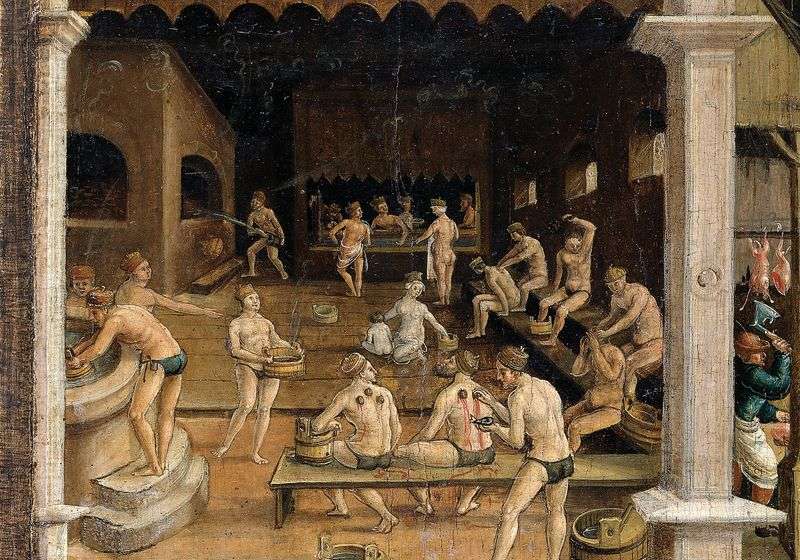

For medieval Europeans, bathing was not only for purification—it was a form of recreation.

Cities contained numerous public bathhouses where people warmed themselves, socialized, and enjoyed relaxation and entertainment.

Image: Public bathhouse scene — Public Domain

Records show that 14th-century Paris had more than 20 public bathhouses. Bathhouse owners formed guilds and regulated operations.

According to the trade regulations of Paris (Le Livre des Métiers), rules prohibited calling customers before dawn and banned the employment of prostitutes or vagrants inside bathhouses—showing that public bathing was controlled for safety and morality.

Bath fees cost around 2–4 deniers (roughly equivalent to 300–800 yen today), making them accessible to common citizens.

Bathhouses were lively spaces, sometimes gender-separated and sometimes mixed.

Warm herbal baths filled the air with fragrance, tables lined the walls for meals, and bread and wine were served.

Bathing was not merely hygiene. It was community—the pleasure of conversation, food, and warmth shared together.

5. Conclusion

Image: Alfred Stevens, “La Baignoire,” c.1870 — Public Domain

From the Renaissance onward, the meaning of bathing gradually shifted from religious purification to everyday health and hygiene.

Yet the medieval culture of water and fragrance lived on quietly in later Europe.

Perfume, herbal bathing, and soap culture were direct descendants of medieval ideas of cleanliness.

Behind them lay a subtle aesthetic reverence for water and scent, and a spiritual desire for purification.

The roots of what we now call “cleanliness” were already alive in the daily lives of medieval people.

Sources:

Étienne Boileau, Le Livre des Métiers

Le Ménagier de Paris

Eleanor Janega, “I Assure You, Medieval People Bathed”, etc.