【The Enigmatic World of Courtesans in Belle Époque Paris】

Late 19th-century Paris was a city of glittering contradictions.

While artists debated in cafés and aristocrats gathered in salons, behind the velvet curtains stood the mysterious figures known as courtesans. These women were far more than mere companions—they were trendsetters, intellectuals, and in some cases, influencers of national politics.

Gifted with beauty, intelligence, and charm, the women known as courtesans navigated the elite circles of French society with calculated brilliance. But who exactly were they?

【What Is a Courtesan?】

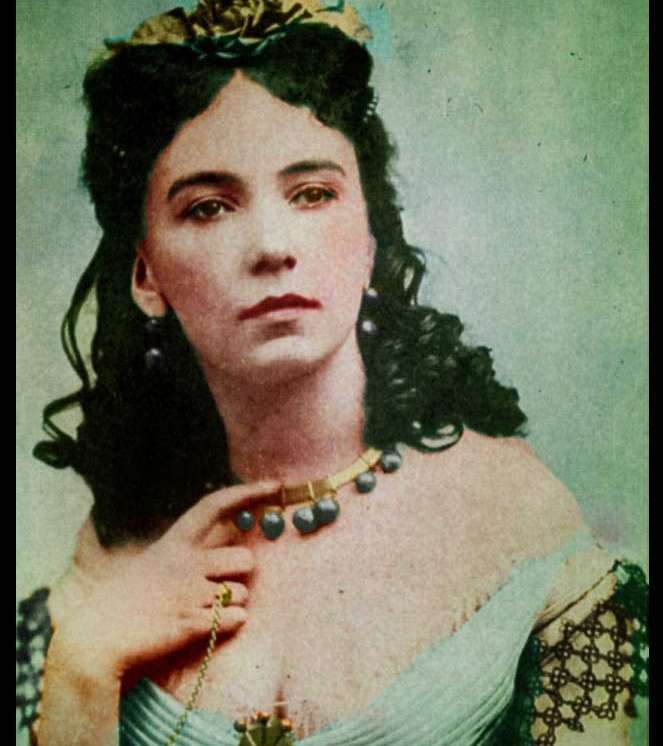

Madame du Barry (public domain)

The term courtesan originated in medieval France, originally referring to a woman of the court. Over time, it came to describe women who engaged in romantic and financial relationships with aristocrats or wealthy patrons.

But they were never just prostitutes. These women combined striking beauty with refinement, education, etiquette, and social grace. They were welcomed as equals in elite salons and cultural circles.

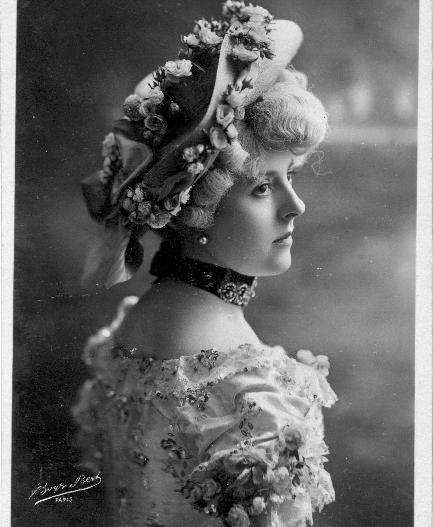

Many came from humble backgrounds or began as stage performers. Once noticed by influential men, they were often mentored, educated, and transformed into elegant ladies indistinguishable from nobility. Prominent figures like Madame de Pompadour and Madame du Barry, mistresses of Louis XV, are often cited as historical courtesans.

Madame de Pompadour (public domain)

While Japan’s oiran of the Edo period might offer a loose comparison, courtesans in France differed significantly: they operated independently, bound to a single patron rather than a brothel system, and often lived in luxurious freedom.

To become a courtesan, a woman had to be noticed by the right man, then refine herself in manners, language, and knowledge. Beauty alone was never enough—success required charisma, self-awareness, and luck.

【The Golden Age of Courtesans】

After the turbulence of the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars, France swung between monarchy and republicanism. During the Second Empire under Napoleon III, Paris underwent sweeping modernization under Baron Haussmann, emerging as a modern city of stone boulevards and gas lamps.

But the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 brought down the Empire, ushering in the Third Republic.

Paris Exposition, 1900 (public domain)

Despite political instability, the late 19th century saw economic growth and cultural prosperity. This era, known as La Belle Époque, was when the courtesans shone brightest.

They weren’t just lovers to aristocrats, politicians, and artists—they were intellectual companions, influencers, and hosts of salons where ideas and fortunes collided. Their beauty was matched by wit, musicality, and literary knowledge, making them muses and confidantes alike.

Their jewels and mansions were legendary, their names splashed across gossip columns. Courtesans conversed as equals with novelists and painters and sometimes even shaped political thought.

One famous example is Édouard Manet’s 1863 painting Olympia.

Olympia by Édouard Manet (public domain)

Depicting a nude woman boldly meeting the viewer’s gaze, Olympia was a stark challenge to traditional ideals. Many critics interpreted it as a statement of pride and agency among women who sold their bodies by choice, not desperation.

【The Women Who Defined the Era】

Let’s explore the lives of three of the most iconic courtesans from the Second Empire through the Belle Époque.

Cora Pearl (public domain)

Cora Pearl

Born Emma Elizabeth Crouch in Britain, Cora Pearl became the embodiment of Parisian decadence in the Second Empire.

She was romantically involved with Prince Napoleon-Jérôme and the Duke of Morny—Napoleon III’s half-brother—and lived a lavish life that captivated the city. She is believed to be one of the inspirations for Émile Zola’s Nana.

After surviving sexual trauma in her youth, Cora realized the power of her beauty. She took to the stage in Paris under her new name, where her allure—more than her acting—captured the attention of wealthy elites.

She quickly rose to the top, allegedly earning 5,000 francs (equivalent to around ¥20 million today) in a single night. Her cold demeanor toward patrons made her all the more irresistible.

In her later years, her young lover Alexandre Duval attempted suicide outside her home—a scandal that forced her into exile in London. She eventually returned to a changed France, where the Empire was gone and her influence had faded.

She died of colon cancer in 1886, buried in a communal grave with no headstone.

Émilienne d’Alençon (public domain)

Émilienne d’Alençon

Born Émilienne André in 1869 to a poor family in Paris, she began performing in her teens and became one of the famed “Three Graces of the Belle Époque.”

Loved by Belgium’s King Leopold II and admired in fashion circles, Émilienne was more than a beauty—she was a cultural icon. She was also the mistress of businessman Étienne Balsan and is credited with introducing the then-unknown Coco Chanel to Paris society.

Around 1908, she was rumored to have had a romantic relationship with poet Renée Vivien, defying norms and living on her own terms.

She later married jockey Percy Woodland, who died in 1914. Émilienne lived out her later years peacefully and died in Nice in 1946.

Cléo de Mérode (public domain)

Cléo de Mérode

Born in 1875 in Paris, Cléo de Mérode mesmerized audiences with her otherworldly beauty.

She joined the Paris Opera Ballet School at age 7 and appeared on stage as a child, though her skills as a dancer were considered average. Still, her presence inspired painters, photographers, and sculptors alike. In 1896, she was named “the most beautiful woman in France.”

Though she used the noble-sounding name “de Mérode,” it’s unclear whether she had aristocratic blood. According to her autobiography, her mother served in the Austrian court and Cléo was allegedly the child of a nobleman—but no proof has surfaced.

Rumors of a relationship with King Leopold II swirled throughout her life, but Cléo always denied them. She rejected the label of courtesan and fought fiercely for her dignity.

When Simone de Beauvoir labeled her a “noble-born courtesan” in The Second Sex, Cléo sued for defamation—and won.

She lived a quiet life in Paris, continuing to dance and study music until her death at age 91. She is buried at Père Lachaise Cemetery and remains a symbol of Belle Époque elegance.

【The End of the Courtesan Era】

As the Belle Époque drew to a close, so too did the age of the courtesan.

It wasn’t simply a change in taste—it was a seismic social shift. The First World War in 1914 swept away the glamor of high society. Austerity and sacrifice replaced indulgence and patronage. The aristocrats who had supported the courtesans faded into history.

World War I (public domain)

Women’s roles also changed. With increased access to education and employment, women began to pursue independence. No longer reliant on male patrons, the traditional path of the courtesan became outdated.

Courtesans may not have been paragons of morality—but they wielded beauty and intellect to shape culture, sometimes even politics. They were not prostitutes, nor mere mistresses. They were cultural figures—symbols of a dazzling and complex era.

References :

Kyoko Murata, The Courtesan Image in La Dame aux Camélias and Manon Lescaut, Journal of French Literature (Kyoto University)

Masaru Yamada, Demi-Mondaines: Women of Paris’s Shadow Society, Hayakawa Publishing

Shigeru Kashima, The Monstrous Emperor: Napoleon III and the Second Empire, Kodansha

Florent Fels, trans. by Takamitsu Fujita, Belle Époque Illustrated: Paris in 1900, Yasaka Publishing