In today’s world, beauty is promoted through mass media—TV, magazines, and social media influencers. But in 18th-century Japan, none of these platforms existed. Instead, a powerful visual medium called ukiyo-e (woodblock prints) became the face of pop culture and fashion trends.

Among the most iconic examples is a print known as the Three Beauties of the Kansei Era, created by the legendary artist Kitagawa Utamaro in the 1790s. The portrait features three real-life women from Edo (now Tokyo), whose stunning looks and unique charm captured the imagination of an entire nation.

But behind the art was a strategy. These women didn’t become famous by accident—they were discovered, promoted, and immortalized through a calculated collaboration between Utamaro and a savvy publisher named Tsutaya Jūzaburō.

【Beauty as a Visual Campaign】

In every era, beauty captivates. During the Edo period, being “beautiful” wasn’t just about appearance—it was a form of public influence. Artists like Utamaro helped define national beauty standards, not unlike how celebrities or influencers shape ideals today.

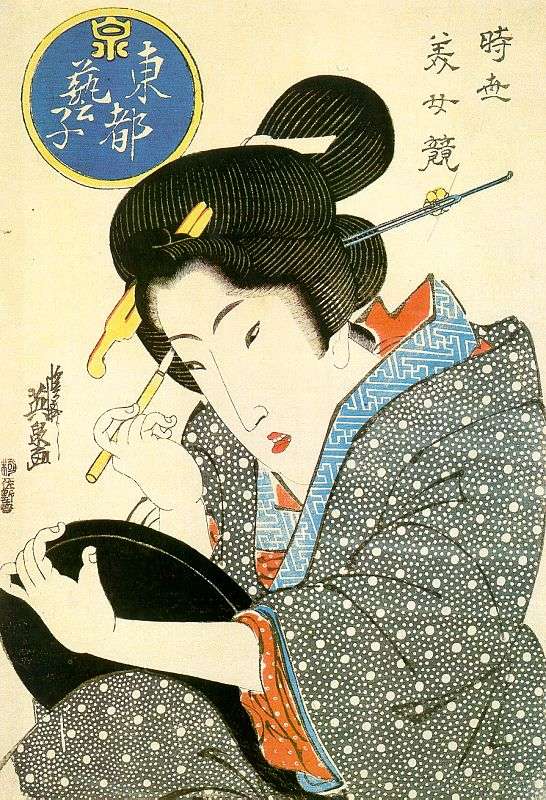

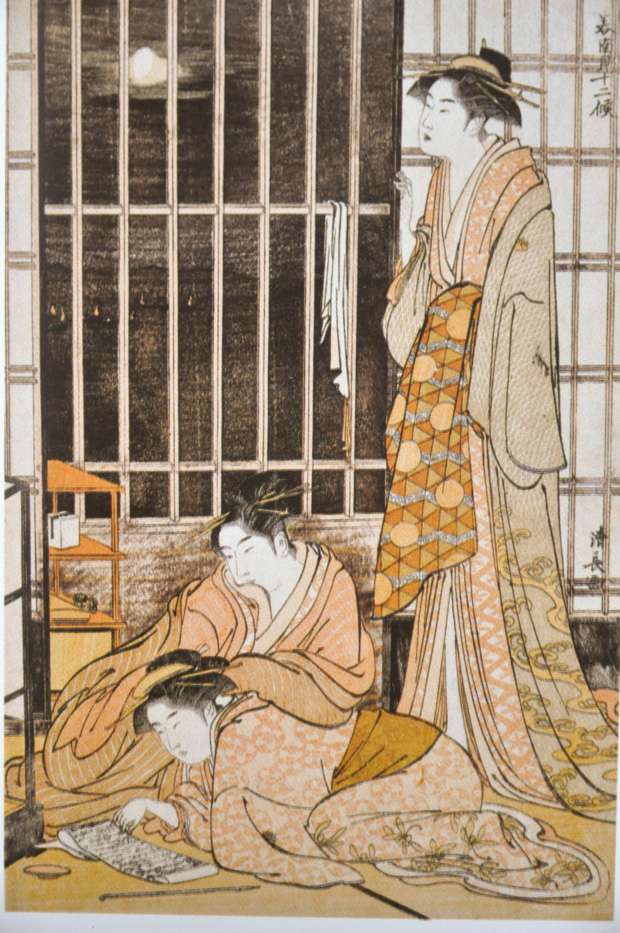

At the heart of this cultural movement was the genre of bijinga, or “pictures of beautiful women,” which became one of the most beloved themes in ukiyo-e.

Suzuki Harunobu, “Amayo no Miya Mōde” Wikimedia Commons

Hishikawa Moronobu, “Mikaeri Bijin” Wikimedia Commons

Keisai Eisen, “Tōto Geiko” from Jisei Bijin Kurabe Wikimedia Commons

Torii Kiyonaga, “Minami Jūni-kō: Ninth Month” Wikimedia Commons

Yet it was Utamaro who revolutionized the form.

Utamaro’s most famous contribution is undoubtedly his portrait of the “Three Beauties of the Kansei Era.” These weren’t mythical figures or royalty—they were actual women from Edo’s bustling cityscape:

Tomimoto Toyohina, a celebrated geisha trained in Jōruri music.

Takashimaya Ohisa, the daughter of a rice cracker vendor and the star of a teahouse in Edo’s Yagenbori district.

Naniwaya Okita, a teahouse server near the Asakusa temple gate.

Each woman came from modest backgrounds, but their refined features—pale skin, delicate oval faces, and narrow, upward-slanting eyes—fit the era’s aesthetic ideals.

【Subtle Differences in Style and Identity】

Though the women appear similar at first glance, Utamaro included subtle markers to distinguish each one.

Kitagawa Utamaro, annotated view of “Three Beauties” Wikimedia Commons

Tomimoto Toyohina wears a pattern of primrose flowers (sakurasō).

Takashimaya Ohisa is adorned with the paulownia crest (kiri).

Naniwaya Okita holds a fan featuring the oak leaf crest (kashiwa).

These emblems weren’t just decorative—they served as visual identifiers, much like logos or brand symbols today.

Utamaro also captured differences in expression, posture, and facial structure. The shape of the eyebrows, the contour of the cheeks, and even the tilt of the head were carefully designed to express individuality.

Kitagawa Utamaro, portraits of Okita, Ohisa, and Toyohina Wikimedia Commons

He used a technique called ōkubi-e (large-head portraits), which zoomed in on a woman’s face and upper body—a rarity at the time.

【When Beauty Became a Business Strategy】

At the time, Utamaro was still a relatively unknown illustrator, creating book illustrations for other publishers. But Tsutaya Jūzaburō saw his potential. Tsutaya had recently faced severe censorship by the government and had lost half his assets due to publishing satirical and risqué books. Supporting Utamaro and his provocative bijinga was a bold comeback strategy.

Chōbunsai Eishi, Portrait of Kitagawa Utamaro (age 60) Wikimedia Commons

Their collaboration was more than just art—it was branding. The three women became cultural celebrities. Their hairstyles, kimono patterns, and even accessories became fashion statements for women across Edo.

One of the most famous examples is Utamaro’s “Woman Blowing a Glass Toy,” where the featured woman wears a bold checkered kimono and plays with a vidro (a Portuguese glass toy). The image was so popular that it influenced real-life trends in dress and decoration.

Kitagawa Utamaro, “Woman Blowing a Glass Toy” Wikimedia Commons

【Legacy Beyond the Print】

Ukiyo-e prints like Utamaro’s weren’t just posters—they were media events. They made ordinary women into icons. These portraits were collected, discussed, and even reinterpreted like pop culture memorabilia.

Utamaro’s work pushed boundaries in form, technique, and emotion. Using kirazuri (mica printing), he added shimmering textures that enhanced the prints’ visual appeal. His focus on close-up expressions and subtle gestures gave a sense of inner life—rare in portraiture at the time.

Tsutaya Jūzaburō’s publisher’s seal – Mount Fuji shape with ivy leaf Wikimedia Commons

Thanks to Utamaro and Tsutaya’s strategic partnership, these three women—once working-class entertainers—became symbols of beauty for an entire generation.

They weren’t queens, but they became the faces of a nation.

References :

The Cultural History of Japanese Cosmetics, POLA Research Institute

Tsutaya Jūzaburō and the World of Ukiyo-e, Nayuta Publishing