Chapter 1: Mao Zedong’s Personal Physician

Image: Portrait of Mao Zedong published in the Quotations from Chairman Mao, 1955 public domain

Li Zhisui was the personal physician of Mao Zedong, the leader of China at the time.

From 1954 until Mao’s death in 1976, Li played a crucial role in managing the Chairman’s health.

He was not only responsible for medical care but also witnessed Mao’s daily life, personality, and inner circle.

After Mao’s death, Li continued to practice medicine in China before immigrating to the United States in 1988.

There he published memoirs revealing Mao’s health issues and political background, later translated as “The Private Life of Chairman Mao.”

Because the content was considered highly sensitive, the book was banned in China.

Yet, Li’s personal perspective as Mao’s physician makes his account an invaluable historical record, even if it must be read with caution.

This article draws on Li’s memoir to describe Mao Zedong’s final days.

Chapter 2: Declining Health and the Medical Team’s Struggle

Image: The Monument to the People’s Heroes, inscribed by Mao Zedong CC BY-SA 3.0

In his later years, Mao suffered from chronic bronchitis and emphysema caused by decades of heavy smoking.

His left lung was severely damaged, forcing his right lung to overwork and leaving him with consistent respiratory issues.

To aid him, the medical team used an American-made respirator, originally provided during Henry Kissinger’s secret visit to China in 1971.

By 1974, Mao was also diagnosed with motor neuron disease, which gradually robbed him of the ability to speak and move.

On June 26, 1976, Mao suffered his second heart attack, leaving him even weaker.

His medical team worked around the clock, with Li sleeping on a simple cot in the ward to remain on constant watch.

Chapter 3: The Intervention of His Wife, Jiang Qing

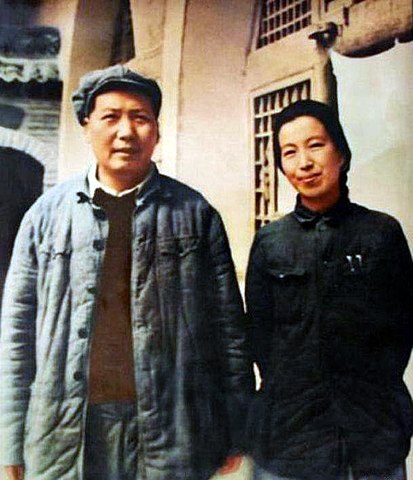

Image: Mao Zedong and Jiang Qing public domain

Mao’s medical treatment was never just a medical issue — it was entangled with politics.

His wife, Jiang Qing, often visited the sickroom, pressuring doctors and issuing her own commands.

According to Li, she accused the medical staff of exaggerating Mao’s illness and insisted he was stable.

She even forced nurses to conduct her own health checkups and demanded that political documents be shown to Mao despite his suffering condition.

On September 2nd, Mao suffered his third heart attack.

From then on, he could only breathe properly when lying on his left side, with mechanical assistance required to keep him alive.

On the night of September 8th, Jiang Qing intervened once more.

She insisted that Mao be turned onto his right side.

When staff complied, Mao’s breathing stopped.

Emergency procedures revived him briefly, but Li suggested this incident may have hastened his death.

Chapter 4: September 9, 1976

Image: Electrocardiogram monitor, stock photo AC

By the early hours of September 9th, Mao’s condition was beyond hope.

Li and the nurses attempted emergency drugs to sustain his blood pressure, but they had little effect.

At 12:10 a.m., Mao Zedong’s heart stopped, and the leader of modern China passed away.

By his bedside stood Hua Guofeng, Mao’s designated successor, along with Wang Dongxing, Wang Hongwen, and Zhang Chunqiao — two key figures of the “Gang of Four.”

Even as Mao’s life ended, urgent political discussions began immediately.

The Chinese government officially announced his death as the result of a heart attack and Parkinson’s disease.

Chapter 5: The Political Aftermath

Image: Portraits of Hua Guofeng and Mao Zedong displayed side by side, 1978 wiki c LBM1948

Mao’s death shook China, where he had been respected as a godlike figure, and triggered a rapid shift in the Communist Party’s balance of power.

Hua Guofeng consolidated leadership, claiming legitimacy from Mao’s note that read, “With you in charge, I am at ease.”

But doubts remained.

Meanwhile, Jiang Qing and the Gang of Four tried to seize control by invoking Mao’s authority.

Hua and Wang Dongxing struck back quickly.

Just one month after Mao’s death, in October 1976, the Gang of Four were arrested in what was essentially a palace coup.

This marked the definitive end of the Mao era and the beginning of China’s next chapter.

While Mao’s death left a deep sense of emptiness, it also forced the nation to confront the urgent need for reform and reconstruction.

China’s path forward would unfold under Mao’s legacy.

Reference: The Private Life of Chairman Mao by Li Zhisui