At the end of the 3rd century BCE, ancient China was plunged into chaos after the death of the First Emperor of Qin. In the power vacuum that followed, two titanic figures emerged: Xiang Yu, the self-proclaimed “Hegemon-King of Western Chu,” and Liu Bang, the man who would go on to found the Han Dynasty.

Though Xiang Yu was an unmatched warrior—claiming he had never lost a single battle in over seventy engagements—he ultimately fell to Liu Bang. Why did the strongest general of his time fail to seize the empire?

This article traces the rise and fall of Xiang Yu and explores how a man feared on the battlefield was undone by politics, strategy, and fate itself.

1. The Uprising Begins

Image: Qing dynasty portrait of Xiang Yu (public domain)

Xiang Yu was born into a distinguished military family that had served the state of Chu for generations.

When he was ten years old, his homeland of Chu was conquered by the Qin empire. Forced to flee, he relocated with his uncle, Xiang Liang, to the southern region of Wu in Kuaiji Commandery.

Over the next decade, Xiang Yu and his uncle built up their strength.

In 209 BCE, taking advantage of the widespread unrest caused by the Chen Sheng and Wu Guang Rebellion, they seized control of Kuaiji and launched an uprising.

With 8,000 hand-picked elite troops, they crossed the Yangtze River and marched north. Along the way, they defeated rival forces like those of Chen Ying and Ying Bu, who would later become key figures in Chinese history.

They also crushed the faction of Jing Ju, who had declared himself king of Chu.

During this period, another rising figure—Liu Bang—also joined Xiang Liang’s forces.

Image: Liu Bang, founder of Han (public domain)

In 208 BCE, under the advice of strategist Fan Zeng, Xiang Liang located a descendant of Chu royalty—an anonymous shepherd—and installed him as King Huai II to restore legitimacy to their cause.

Xiang Liang’s forces swelled to more than 100,000, and the anti-Qin campaign intensified.

With a royal figurehead in place and the military growing stronger, it seemed that Xiang Yu’s path to glory was firmly set.

【2. The Death of Xiang Liang】

Image: Xiang Liang slain in ambush (Photo by the author)

Just as the momentum was building, Xiang Yu received shocking news: his uncle Xiang Liang had been killed.

The seasoned Qin general Zhang Han launched a surprise night attack, killing Xiang Liang in battle.

With his uncle gone, Xiang Yu inherited the command of the army—but this would mark a turning point in his career.

King Huai II, the nominal leader of the Chu cause, began to grow wary of Xiang Yu’s rising influence.

To balance his power, the king promoted former rivals and political survivors: remnants of the Chen Sheng rebellion like Lü Chen, and former Chu statesmen such as Song Yi.

Xiang Yu’s enemies were no longer limited to the Qin.

Even his own allies—his king and fellow generals—could become political obstacles.

Yet it’s unclear whether Xiang Yu fully understood the shifting dynamics around him.

King Huai II appointed Song Yi as supreme commander of the relief army to aid Zhao at Julu, placing Xiang Yu as a secondary general and Fan Zeng as third in command.

Although Song Yi had no battlefield experience, Xiang Yu did not object to this unfair appointment.

At the same time, Liu Bang began marching west with his own army.

King Huai II issued a decree: “Whosoever enters the Qin heartland (Guanzhong) first shall be made its king.”

This statement—later known as the “Covenant of Huai”—would become a key issue in the unfolding struggle.

At the time, many believed the decree was merely symbolic, intended to inspire the troops.

After all, the Qin had not yet fallen. But this symbolic promise would later shape the political outcome of the entire war.

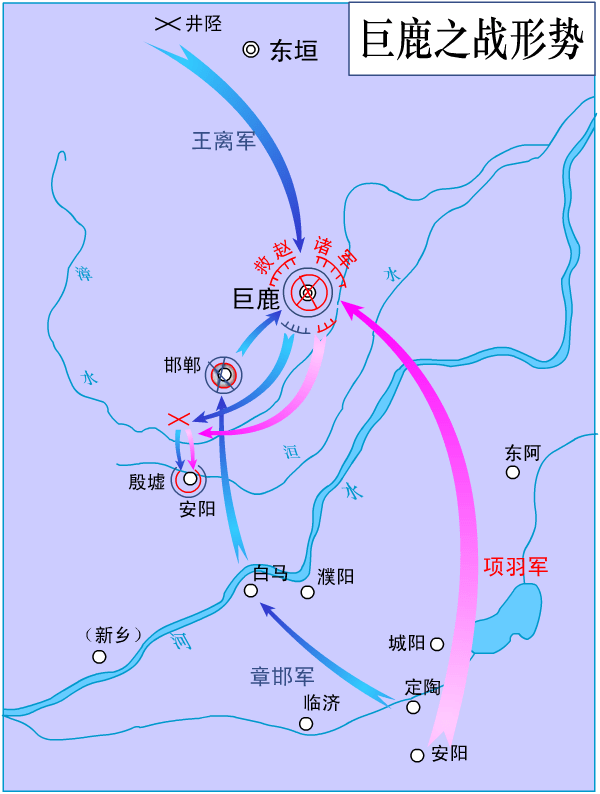

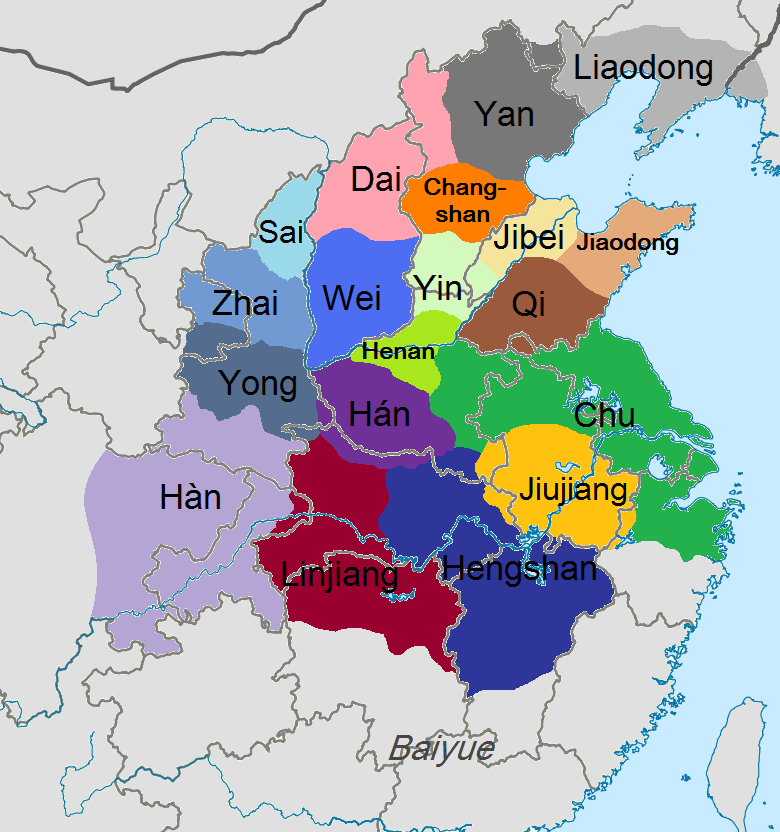

3. The Battle of Julu

Image: Map of the Battle of Julu (wiki c Zhuwq)

Following King Huai II’s orders, Xiang Yu joined Song Yi and encamped at Anyang, near the border with the state of Qi.

However, Song Yi made no move for 46 days.

Rather than aiding Zhao, he remained in place, secretly negotiating an alliance with Qi. He even sent his son to Qi, hoping to secure a future appointment as chancellor.

Xiang Yu, enraged by the inaction and selfish motives, condemned Song Yi in front of the troops:

“Any commander who ignores the suffering of his soldiers and plots only for his son’s advancement is unworthy to serve the state!”

With that, Xiang Yu executed Song Yi on the spot and seized command of the army.

He immediately marched to Julu, where Zhao was besieged by a massive Qin force, estimated at 200,000 to 300,000 soldiers.

Xiang Yu launched a ferocious assault and achieved a miraculous victory, crushing the Qin army and forcing the surrender of their commander, Zhang Han.

In a controversial move, Xiang Yu named Zhang Han “King of Yong” and placed him under his own authority.

At this moment, Xiang Yu possessed the strongest military force in all of China.

But his political position was much more fragile.

He had executed Song Yi without orders. He led the coalition forces without official sanction. He appointed a surrendered Qin general as a king—all of these decisions were made unilaterally.

Even if Xiang Yu did not intend rebellion, these actions could easily be seen as insubordination by King Huai II.

His legitimacy, after all, came from the very monarch whose authority he was undermining.

Still, there was no one left who could challenge Xiang Yu’s dominance on the battlefield.

4. The Fall of Qin

Image: Historical painting by Kimura Buzan (public domain)

In October of 206 BCE, Xiang Yu led a massive coalition army of 400,000 men westward into the Qin heartland.

By December, he arrived at Hangu Pass—the eastern gateway to the Qin capital.

But instead of Qin troops, he found Liu Bang already occupying the region.

Liu Bang had bypassed the pass, marched into Guanzhong, and forced the surrender of the Qin king, Ziying.

Citing King Huai II’s earlier decree, Liu Bang now claimed the region as his own and blocked Xiang Yu’s advance.

Xiang Yu was furious.

He stormed through the pass and advanced toward Xianyang, determined to punish Liu Bang.

However, his uncle Xiang Bo intervened, urging restraint. Liu Bang, for his part, sent word of surrender through Xiang Bo and invited Xiang Yu to a banquet—a tense political meeting known as the Feast at Hongmen.

Xiang Yu ultimately spared Liu Bang.

But after entering the Qin capital, he looted the city and set fire to the royal palace.

His troops began a spree of violence and plunder, devastating the local population.

While Xiang Yu alienated the people of Guanzhong, Liu Bang—who had refrained from pillaging—grew increasingly popular.

With the Qin dynasty officially extinguished, Xiang Yu now held power over all of China.

He declared himself the “Hegemon-King of Western Chu” and distributed kingships to other warlords who had participated in the anti-Qin campaign.

But then came a final command from King Huai II:

“Honor the promise—make Liu Bang the King of Guanzhong.”

Xiang Yu scoffed.

“What claim does a man with no military merit have to such power? The fate of the realm lies with the warlords and with me—not with a broken promise from a powerless king.”

From that moment, King Huai II was no longer a monarch in Xiang Yu’s eyes—he was a rival.

5. The Chu-Han Conflict

Image: Xiang Yu dividing the empire into 18 kingdoms (wiki c Nederlandse Leeuw)

After the fall of Qin, Xiang Yu elevated King Huai II to the honorary title of “Emperor Yi” but stripped him of real power.

Xiang Yu then declared himself the Hegemon-King of Western Chu and divided China into 18 regions, appointing kings from among his allies and former enemies.

However, his political decisions were deeply flawed.

He rewarded those who had supported him personally, regardless of merit, and punished or ignored those who had achieved great things but didn’t align with him.

Liu Bang was exiled to the remote region of Hanzhong.

Other powerful leaders—like Tian Rong in Qi and Peng Yue in Liang—were either marginalized or provoked.

Dissatisfaction spread quickly. Rebellions flared.

The empire Xiang Yu had just “unified” began slipping from his grasp almost immediately.

Even worse, just months later, Xiang Yu had Emperor Yi—formerly King Huai II—sent to a remote location and secretly killed by Ying Bu, one of his generals.

Though Xiang Yu had removed a political thorn from his side, the consequences were disastrous.

Liu Bang seized the opportunity.

He accused Xiang Yu of regicide and rallied warlords to his cause.

This gave Liu Bang not just military strength, but a clear moral claim to leadership.

In April 205 BCE, while Xiang Yu was busy suppressing a rebellion in Qi, Liu Bang and his allies struck.

They captured Xiang Yu’s capital of Pengcheng, signaling the start of the Chu-Han War.

Upon hearing the news, Xiang Yu rushed back with only 30,000 elite troops and, in an astonishing feat of speed and force, crushed Liu Bang’s coalition of 560,000 men at the Battle of Pengcheng.

Image: Cavalry charge (Photo by the author)

Though Liu Bang managed to escape and regroup with help from his brother-in-law Lü Ze, the damage to Xiang Yu’s strategic position was already done.

Liu Bang then persuaded Ying Bu—who had once been Xiang Yu’s close ally—to defect to his side.

Xiang Yu had now lost yet another critical commander.

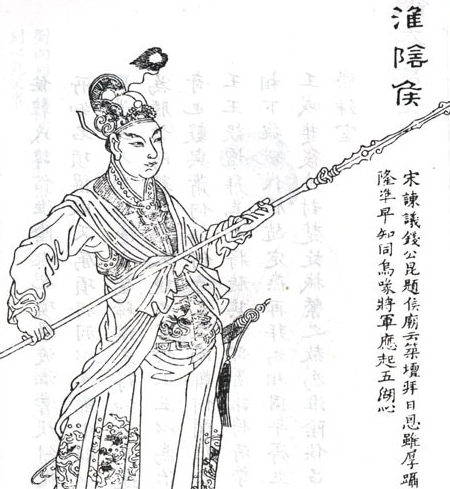

6. Surrounded on All Sides

Image: Han Xin (public domain)

While Xiang Yu was focused on the central front, the balance of power began shifting.

Liu Bang’s rising general, Han Xin, launched a series of stunning campaigns.

He conquered Wei, Zhao, and Yan in the north, then turned his attention to Qi.

At the same time, Peng Yue disrupted Xiang Yu’s supply lines, destroying food stocks and cutting off reinforcements.

When Xiang Yu attempted to retaliate against Peng Yue, Liu Bang seized the opportunity to strike Xiang Yu’s weakened main forces.

To make matters worse, Liu Bang’s advisor Chen Ping orchestrated a major psychological campaign—sowing distrust and disunity among Xiang Yu’s officers.

One by one, Xiang Yu’s inner circle began to collapse.

His trusted strategist Fan Zeng departed the army.

Top generals like Zhongli Mo and Zhou Yin grew distant or resentful.

Within just one year, Xiang Yu found himself surrounded—not only by enemy forces, but also by growing isolation in his own camp.

Then, in 203 BCE, Han Xin led a massive assault on Qi and annihilated a 200,000-strong Chu army.

Xiang Yu was critically weakened.

Desperate and under pressure, he agreed to a peace deal proposed by Liu Bang.

But Liu Bang had no intention of keeping it.

Shortly after the truce, Liu Bang mobilized a massive army—joined by Han Xin, Peng Yue, Ying Bu, and even former Chu generals like Zhou Yin.

Xiang Yu, exhausted and outnumbered, was surrounded on all sides.

In December 202 BCE, the final blow fell.

Xiang Yu made his last stand and was ultimately defeated and killed.

The exact site of his death is debated—some sources cite Gaixia, others mention Chenxia—but either way, the Chu-Han War came to a dramatic end.

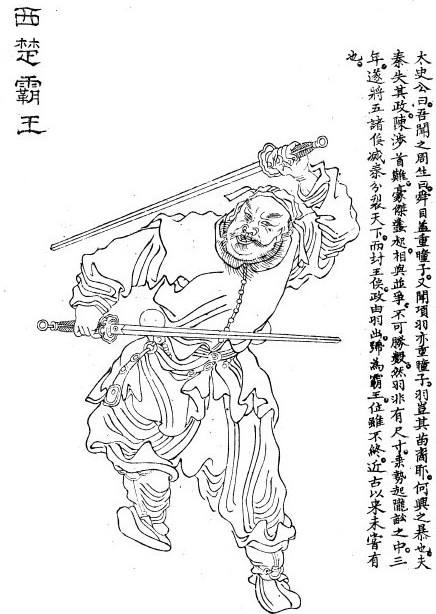

7. Heaven Destroyed Me

Image: Xiang Yu (public domain)

Looking back on Xiang Yu’s life, there is little doubt: he was the most powerful warrior of his era.

But he was not a politician.

His political blunders were numerous and severe.

He killed his superior, Song Yi, to seize command.

He unilaterally made decisions over appointments and territory.

He provoked rebellion by mishandling postwar rewards.

He murdered King Huai II, his own nominal ruler.

Had his uncle Xiang Liang lived longer, perhaps Xiang Yu might have matured politically under his guidance.

But instead, Xiang Yu was thrust into power without the experience or temperament to wield it wisely.

After Xiang Liang’s death, this young, impulsive warrior had to navigate a brutal power struggle among seasoned, cunning rivals.

Even if he had bowed to authority, King Huai II and Song Yi likely still would have tried to suppress or eliminate him.

In that context, Xiang Yu may have felt he had no choice but to take power himself.

Furthermore, the very trait that made him great—his unmatched strength—also doomed him.

Xiang Yu’s army was terrifyingly effective, but only when he led them personally on the battlefield.

Whenever he stepped away, his forces weakened, and Liu Bang would surge back.

Over time, this cycle eroded Xiang Yu’s position.

Moreover, Xiang Yu’s leadership style was closed and insular.

He failed to attract or retain talented outsiders.

Figures like Han Xin and Chen Ping, who later served Liu Bang, once spoke admiringly of Xiang Yu’s personal virtues—but criticized his lack of vision.

Han Xin said, “Xiang Yu was kind and respectful, but he didn’t know how to place people in the right positions.”

Chen Ping added, “He failed to reward merit, and thus drove people away.”

His army functioned more like a brotherhood than a state.

Such loyalty can be powerful, but it is brittle when tested by long-term pressures.

And then, there was the pace of history.

From the death of Qin Shi Huang to the end of the Chu-Han War was less than a decade.

Xiang Yu spent almost all of that time in battle, with no real opportunity to learn the art of governance.

According to Sima Qian’s Records of the Grand Historian, in his final moments, Xiang Yu lamented:

“Heaven has destroyed me.”

In the end, it may truly have been fate—along with the era, the system, and his own nature—that brought about Xiang Yu’s downfall.

He perished not despite being Xiang Yu, but because he was Xiang Yu.

References:

Records of the Grand Historian (Shiji) by Sima Qian

Yasuhiko Satake, Liu Bang and Xiang Yu, Chuokoron-Shinsha

Katsuhisa Fujita, The Era of Xiang Yu and Liu Bang, Kodansha

Ryuma Matsushima, The Formation of the Han Empire, Kyoto University Press