Image: Created by the author

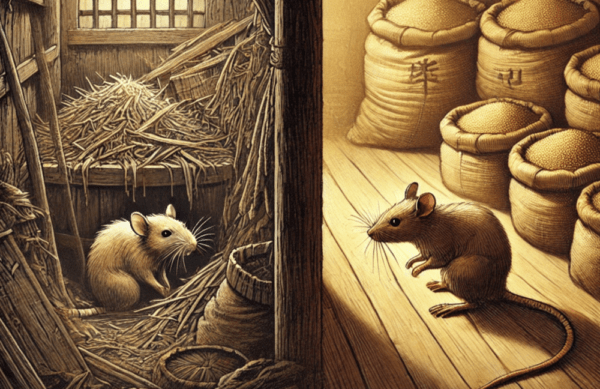

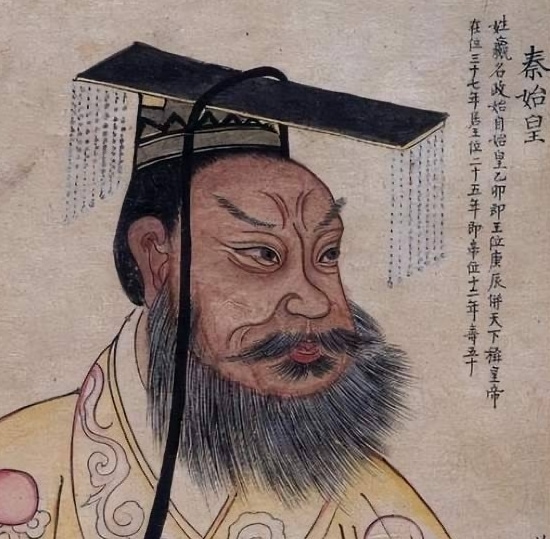

In 221 BCE, China was unified for the first time under one man: Qin Shi Huang.

Ruthless, brilliant, and obsessed with power—he built an empire on strict laws and absolute control.

But just years after his death, the mighty Qin Dynasty collapsed.

Why did it fall so fast?

Some say it was one man’s decision that doomed it all.

A man who had helped build the empire—then helped destroy it.

His name… was Li Si.

Part 1: The Parable of the Rats

Image: Created by the author

Li Si was no ordinary politician.

As the chancellor of Qin, he helped unify China under the First Emperor.

A master of Legalism, he enforced harsh laws, burned books, and crushed opposition.

But where did such a man come from?

His journey began with a pair of rats.

As a young man in the state of Chu, Li Si once saw two rats—one scurrying through a filthy toilet, the other feasting on grain in a storage room.

Both were rats, yet one lived in fear and filth, the other in comfort and security.

At that moment, Li Si realized: a person’s fate depends not on talent—but on the environment.

Driven by this belief, he left Chu and studied under the great philosopher Xunzi.

There, he embraced the philosophy of Legalism: a system where law, not morality, ruled the land.

Eventually, he entered the powerful state of Qin and caught the eye of the king—who would later become Qin Shi Huang.

Li Si rose quickly and helped to build an empire.

But after the emperor’s death, he made a fateful choice, one that would haunt him to the grave.

public domain

As Qin’s empire rose, Li Si became its chief architect.

His guiding principle? Legalism—a system where strict laws replaced moral virtue.

Unlike the old feudal system, where nobles ruled semi-independently, Li Si helped abolish hereditary power and replaced it with a centralized bureaucracy.

Local officials were now appointed by the emperor—not born into privilege.

He standardized the written script, making communication across the empire possible.

He unified weights and measures, which boosted trade and tightened state control.

And above all, he enforced strict, unforgiving laws—where all were equal before the law, regardless of rank or status.

These reforms helped solidify Qin’s rule, and would influence China for centuries.

But Legalism came at a price.

To suppress dissent, Li Si ordered the infamous burning of books and the burial of scholars.

Any philosophy that challenged the state’s authority—especially Confucianism—was seen as a threat.

Hundreds of intellectuals were executed.

Knowledge was silenced.

Obedience was everything.

Under the absolute rule of Qin Shi Huang, these measures were held.

But the system depended on one thing: a strong emperor.

And when that emperor died… the cracks began to show.

Part 3: The Death of the Emperor and the Sand Dune Conspiracy

public domain

In 210 BCE, Emperor Qin Shi Huang set out on his fifth imperial tour.

During the journey, he fell gravely ill and died in a place called Sand Dune—far from the capital.

With him were three men: the eunuch Zhao Gao, the chancellor Li Si, and the emperor’s youngest son, Huhai.

But here’s the secret: the emperor had named his eldest son, Fusu, as his rightful heir.

Fusu was a capable leader, respected by the army and supported by the general Meng Tian.

He also sympathized with Confucian ideas—and opposed Li Si’s harsh Legalist policies.

Zhao Gao feared Fusu.

If Fusu became emperor, Zhao’s past crimes would be exposed, and he would surely lose power—or worse.

So Zhao Gao hatched a plan.

He persuaded Li Si to forge a fake imperial decree, declaring that Fusu and General Meng Tian must commit suicide.

At first, Li Si hesitated.

But Zhao Gao played on his fears—fears that under Fusu’s rule, he would lose his position, his power, and maybe even his life.

And so, the two men covered up the emperor’s death… and installed Huhai as the new emperor—Qin Er Shi, the Second Emperor.

They brought the emperor’s corpse back to the capital, hiding the smell with carts full of rotting fish.

The throne was secured.

But the damage had already been done.

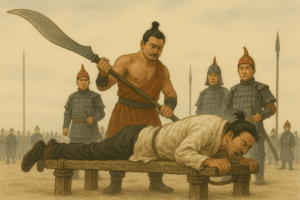

Part 4: Li Si’s Final Fall

public domain

Emperor Huhai—Qin Er Shi—was weak, paranoid, and easily manipulated.

Real power now rested in the hands of Zhao Gao.

Image: Created by the author

At first, Li Si tried to advise the young emperor, and gave a warning of Zhao Gao’s growing control.

But it was too late. Zhao Gao struck first.

He accused Li Si’s son of conspiring with rebels.

Huhai believed the charge, and ordered Li Si’s arrest.

In prison, Li Si wrote a long memorial listing his achievements and begging for mercy.

Zhao Gao intercepted it and ensured it was never seen.

Tortured and broken, Li Si finally confessed to crimes he didn’t commit.

He and his entire family were sentenced to death.

In 208 BCE, Li Si was executed by waist chop—a brutal punishment where the body is sliced in half at the waist.

Image: Created by the author

As he was led to the execution ground with his son, he is said to have sighed:

“I miss the days when we hunted rabbits with our hounds in the fields of Shangcai.”

The man who helped unify China died under the very system he built.

Li Si had believed that law could outlast any ruler.

But in the end, it was virtue, not law, that he lacked.

And without virtue… even the strongest empire can’t stand.