- 1. Information Gathering: The Essential Weapon of the Sengoku Daimyo

- 2. Ko-ori Castle as a Strategic Information Hub Through His Concubine’s Family

- 3. Victory at Okehazama Through Intelligence, and Surviving His Greatest Crisis the Same Way

- 4. Nobunaga’s Regional Commanders All Masters of Intelligence

- 5. Conclusion

1. Information Gathering: The Essential Weapon of the Sengoku Daimyo

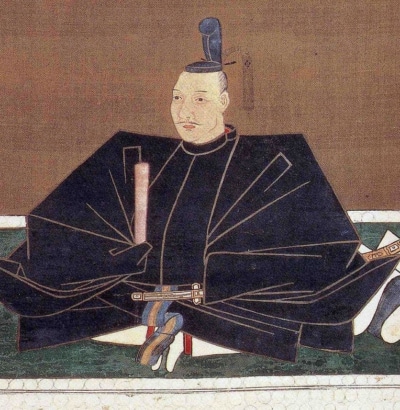

Image: Oda Nobunaga public domain

For the warlords of the Sengoku era, the prosperity or decline of their domains rested entirely on their own capabilities.

In this period, prosperity essentially meant territorial expansion, and achieving that required an acute understanding of the movements and intentions of rival daimyo—whether allies or enemies.

Unlike today, with instant digital communication, the Sengoku period had only one means of gathering information: human networks.

Information traveled through people, and only through people.

As in any age, information held little value if left merely collected. Its true force emerged only through interpretation and strategic use.

Among the many daimyo of the time, Oda Nobunaga distinguished himself for both his ability to gather intelligence and his exceptional skill in using it.

This article examines how Nobunaga acquired information—and how he transformed it into decisive military and political advantage.

2. Ko-ori Castle as a Strategic Information Hub Through His Concubine’s Family

Image: Gate of the Hiroma Residence at the Ko-ori Castle Site (former Shimoyashiki Nakamon) wiki.c

The mothers of Nobunaga’s eldest son Nobutada and second son Nobukatsu were daughters of Ikoma Iemune, lord of Ko-ori Castle in present-day Konan City.

Her exact name is uncertain, but the *Buko Yawa* identifies her as Yoshino, known posthumously as Kuan Keisho, and describes her as one of Nobunaga’s concubines.

According to the same source, Iemune was not only a castle-holding local lord but also a warrior-merchant dealing in ash, oil, and *umagae*—horse-based transporters who carried goods nationwide.

The Ikoma family’s descendants dispute these claims, insisting that the *Buko Yawa* fabricated such stories to discredit their lineage.

However, the physical reality of Ko-ori Castle suggests otherwise.

Though the Ikoma received a fief of less than 2,000 koku after entering Oda service, Ko-ori Castle itself sprawled across an area equivalent to fifteen Nagoya Domes and consisted of multiple baileys, including the main, second, third, and west enclosures.

A fief of that size could mobilize barely 100 soldiers—far too few to defend such a large complex.

Furthermore, Ko-ori Castle was a flatland residence rather than a fortress suited for prolonged siege warfare.

This strongly implies that the castle housed many non-military residents, likely merchants who traveled throughout Japan.

It almost certainly contained warehouses for ash and oil, as well as storage facilities for goods handled by *umagae*.

Taken together, these details suggest that the Ikoma family, though warriors by class, actively engaged in commerce during the Sengoku era.

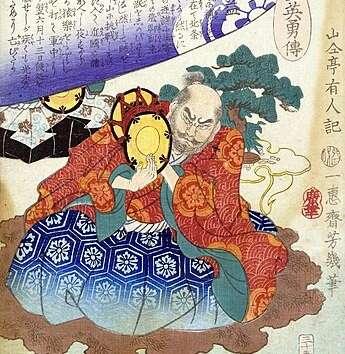

Image: Umagae (from the Ishiyamadera Engi Emaki) public domain

After Nobunaga unified Owari, he frequently visited Ko-ori Castle—not only to meet with his concubine but also for strategic reasons.

Around this time, he set his sights on Kyoto.

After defeating Saitō Tatsuoki of Mino, he adopted the seal **Tenka Fubu**—“Rule the Realm by Force”—symbolizing his ambition to restore the shogunate and unify Japan.

Ko-ori Castle had become a gathering point for merchants who traveled widely across the country.

They brought with them news and observations from distant regions, giving the Ikoma family—and therefore Nobunaga—access to a constant stream of intelligence.

Many of the goods carried by *umagae* were offerings from Kyoto’s court nobles to provincial lords, or the reverse.

This meant that the Ikoma, who coordinated these shipments, inevitably obtained sensitive information about daimyo throughout Japan.

Thus, Ko-ori Castle was not merely a logistical center but one of the largest information hubs in Owari.

Nobunaga most likely analyzed this intelligence carefully, using it to shape his strategies for upcoming campaigns.

3. Victory at Okehazama Through Intelligence, and Surviving His Greatest Crisis the Same Way

Image: Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, “Biographies of Great Warriors: Wild Geese over Yahagi,” depicting Hachisuka Koroku public domain

The Battle of Okehazama—Nobunaga’s dramatic emergence onto the national stage—was won through the full mobilization of his intelligence network.

Among those involved in gathering intelligence were Hachisuka Koroku of the Kawanami group, relatives of the Ikoma, and his brother-in-law Maeno Shoemon.

At the time, they were not yet Oda retainers.

Instead, they supported Nobunaga as independent transport magnates along the Kiso River, acting out of mutual interest.

Koroku dispersed his men across Mikawa Province, where they disguised themselves as peasants, offering sake and food to Imagawa soldiers to lower their guard.

They relayed the army’s movements to Nobunaga, and when the Oda launched their surprise attack, Koroku’s group joined the assault.

Despite this, the highest commendation went to Yanada Masatsuna, an Oda retainer who located Imagawa Yoshimoto’s main camp.

Feeling slighted, Koroku and Shoemon later refused direct service under Nobunaga and instead served Hashiba (Toyotomi) Hideyoshi.

Even so, this episode demonstrates the breadth of Nobunaga’s intelligence efforts.

His surprise attack succeeded because of both the scale of his intelligence network and his ability to analyze and act upon the information he gathered.

Image: Asai Nagamasa public domain

Nobunaga later survived another crisis through the power of intelligence.

During his campaign against Asakura Yoshikage, he was suddenly betrayed by Asai Nagamasa, triggering a desperate retreat at Kanegasaki.

According to the *Asakura-ki*, the first to detect Asai’s betrayal was Matsunaga Hisahide, who oversaw espionage operations in Omi and Wakasa.

Acting on this timely intelligence, Nobunaga immediately ordered a retreat and successfully escaped with the cooperation of Kutsuki Mototsuna of Kutsuki Valley.

Although the Asakura were on the brink of destruction, Nobunaga survived this sudden reversal because of the intelligence network he had meticulously built.

4. Nobunaga’s Regional Commanders All Masters of Intelligence

Image: Toyotomi Hideyoshi public domain

By the eve of the Honnoji Incident, the Oda armies exceeded 200,000 troops, divided into five fronts—Kinai, Chugoku, Hokuriku, Kanto, and Shikoku.

Commanding three of these fronts were Akechi Mitsuhide (Kinai), Hashiba (Toyotomi) Hideyoshi (Chugoku), and Takigawa Kazumasu (Kanto).

All three were recruited during Nobunaga’s rise to national dominance, and Mitsuhide and Hideyoshi were later additions to the Oda hierarchy.

Nobunaga actively sought talent wherever he found it, and these three shared a defining trait:

each had obscure origins and had spent years wandering the provinces, acquiring deep knowledge of local conditions and politics.

Hideyoshi, believed to be of peasant origin, traveled widely as a youth, working as a peddler and servant.

According to the *Buko Yawa*, he entered Oda service through the recommendation of Nobunaga’s concubine while staying at Ko-ori Castle.

His extraordinary rise was due not to battlefield prowess but to his skills in espionage and diplomacy.

Image: Takigawa Kazumasu (from “Taiheiki Eiyu Den 35”) wiki.c

Takigawa Kazumasu’s early life is almost entirely unknown.

His connection to the ninja-rich region of Koka has led some to speculate that he had intelligence training, and he was known as an expert marksman.

Image: Akechi Mitsuhide public domain

Akechi Mitsuhide is traditionally linked to the Toki clan of Mino, but after the fall of Saitō Dōsan, he spent years wandering.

He later came under the protection of Asakura Yoshikage in Echizen, where he likely met Hosokawa Fujitaka, a key retainer of the Ashikaga shogunate.

Through Fujitaka’s connections, Mitsuhide approached Nobunaga and rose rapidly.

His experience, negotiation skills, and intelligence-gathering ability—honed over years of hardship—won Nobunaga’s trust.

5. Conclusion

The commanders who supported the Oda armies at their height were all deeply skilled in espionage, negotiation, and intelligence-gathering.

They built networks across domains, maintained relationships with many daimyo, and collected information that often determined the fate of Nobunaga’s regime.

Yet not all information could safely be reported to Nobunaga.

In the volatile, conspiracy-filled Sengoku era, revealing too much—or the wrong thing—could be fatal, especially under a leader as suspicious and demanding as Nobunaga.

If Akechi Mitsuhide was indeed the mastermind behind the Honnoji Incident, as tradition holds, it is possible that some compromising information found its way to Nobunaga.

Nobunaga wielded information as a weapon in his quest for unification.

But in the end, he may have become the target of the very intelligence web he had woven around himself.

References:

Kaku, Kozo (trans.). Military Tales of the Night: Nobunaga Edition, Modern Japanese Translation. Shin Jinbutsu Ōraisha.

Kuwata, Tadachika. The Shinchōkōki: Newly Edited Edition. Shin Jinbutsu Ōraisha.